Updated Video Link to Taiaiake Alfred’s talk:

Taiaiake Alfred, the world’s foremost expert on the effects of colonization on indigenous peoples, speaks about the ongoing anger felt by people who have been victims of colonization. Listening to Taiaiake speak on the today’s ongoing colonialist experience of Aboriginals (formerly called Inuits) in Canada, I found his points relevant to what is happening today in the Middle East and Africa.

As a Westerner arriving in the Middle East some years ago, I was shocked to find Middle Easterners and North Africans describing the Iraq Wars in two ways–as Americans leading a new Christian Crusade against Muslims, and Americans as neo-colonialists out to “steal” Iraq’s oil. “Why else would a country do these things?” I was told, when I tried to argue with people.

North African and Middle Eastern people are still focused on the Crusades as a recent memory (in the way that Westerners focus on the two World Wars as a recent memory) because of their very recent memory of colonization. Recent colonialist experience colors the judgement of a people about everything in life. This altered mentality creates a way of thinking where they feel that no one ever acts altruistically, that no one (nor any country) ever does something unless they will be able to “benefit” from it personally.

The reason it’s difficult for Americans to understand this colonialist mentality is because our own colonialist experience happened so long ago, and anyone with living memory of it died more than 100 years ago. I would posit that for a society to rid oneself of the colonialist experience and mentality takes at least 150 years. If we could go back and look at American society , post-1776, I think we would see lingering attitudes from the Colonialist experience up all the way until World War I. Those born in 1770, some of whom presumably lived until about 1860, would have told their own grandchildren and great-grandchildren about their memories of the colonialist experience. Those grandchildren born in 1830-1850 would have lived until the early 1900s. I would say that sometime between 1900 and WWI, those old attitudes would have been overcome by other events, and forgotten.

So, how does this extrapolate to Africa and the Middle East today? In my experience, people in the Middle East and Africa seem to have a love-hate relationship with their former colonial power.

A love-hate relationship often exists between the colonizers and the colonized. (Painting by John Frederick Lewis, British Orientalist Painter 1830s to 1860s)

In fact, parts of North Africa were united under nationalist governments for the first time in the 1950s. Prior to this time, these areas existed under feudal warlords.

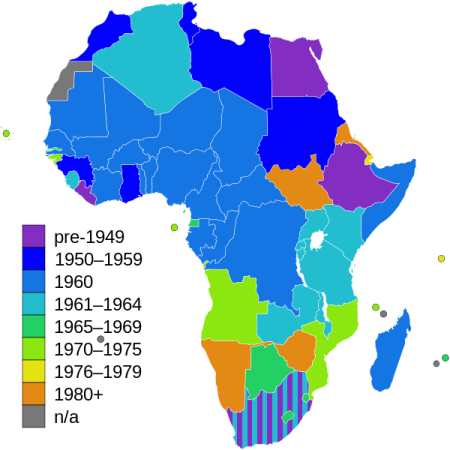

Viewing the independence dates of African countries in the map below, and adding 150 years, shows us that it will take until at least 2100-2130 before Africa is able to begin to shake off its colonialist heritage and the lingering negative effects of the colonialization experience.

A recent colonialist experience creates an anger among a people over their own native culture having been repressed, that no amount of material “goodwill” can ever assuage. In the Middle East and Africa (without mentioning specific examples) there are instances of lands and people being absorbed into a national culture of which those people consider to be a foreign power; these national governments have spent a great deal of money on improving the infrastructure of the absorbed areas–highways, schools, telecommunications, transportation, and modernization–without obtaining any loyalty from the part of the local populations.

Why not? Because these materialist “offerings” do nothing to address the real problem of “forced” assimilation. Native peoples remain alienated.

No doubt this process of forced assimilation and alienation has taken place all over the world, throughout history. But it is not an easy process to recover from, and the effects linger in each locality for up to 200 years afterward. During the North African Spring we have heard much talk of the different tribal areas in Libya, and the problems of forced assimilation during the Gaddafi regime which are now bubbling to the surface. In the past decade we heard of Kurdish problems in Iraq and Turkey. Sometimes we hear of problems with groups in the Sahara. Elsewhere, China has built new infrastructure in Tibet.

According to Taiaiake Alfred, colonized peoples–such as the Aboriginals (formerly called Inuit) and other native peoples of North America–especially believe in treaties, because treaties show respect between two peoples, or two nations. National governments of various societies, on the other hand, believe in integration and assimilation based on social justice principles. The main agenda of national governments is to make formerly colonized peoples into fully-functioning members of society through providing language, education, and job opportunities; however, they show a lack of respect to native peoples by trying to assimilate them. Education is used everywhere as an assimilation tool. “Native peoples living independently is also a threat to national governments because if they live independently, they control more land. This makes less land available for mining claims, for other citizens,” Taiaiake says.

Native leaders who try to work within the national system to obtain more benefits such as land claims and self-government for native peoples are usually viewed as illegitimate leaders by the grassroots population.

Colonized peoples don’t want to be part of an integrative relationship. Their vision is different. their problems are not money problems, or problems of jurisdiction. They are angry about losing their culture and their different way of life. This creates a permanent state of alienation. No matter how many material goods are given, these make no difference, because those material goods never address the source of the problem, the psychological anger.

Furthermore, as these new material things become the norm, the material standard rises ever further. This process prevents getting to the root of the problem–this psychological anger–the pain in the community which comes from losing one’s culture. This causes a permanent state of alienation coming from not having their culture, their values, reflected in the value system of the overall society. This is why there are so many social and psychological problems in the communities which are not being addressed.

In Canada, people wonder why, when the government injects 7. million dollars to relocate a complete band of 700 Inuits to a new location, giving them new housing and other material goods, why the same problems of alcoholism, suicide, depression, and despair emerge again.

Morgan Fawcett, an Aboriginal (Inuit) victim of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome, has dedicated his life to making sure women think before they drink

“It didn’t work because it’s putting the car before the horse,” says Taiaiake. “These people aren’t ready to participate in this government because it’s not a form of government which is reflective of their culture, and their values. It is essentially an imposed form of government. More importantly, the problem of deculturalization of these people has not been fixed.”

Taiaiake says, “When Africa was decolonized, you have societies left that reflect all the worst aspects of the colonizers in the way power is used, in the way that corruption has infused the society.”

Canada’s indigenous people suffer from a post-colonialist mentality, according to Taiaiake. “Native peoples have been illegally dispossessed of their land and treaties have not been honored. We have to address those things before we can have reconciliation.”

“There is always a connection between the means and the ends,” Taiaiake says. “If you want to have a peaceful co-existence with your neighbor, you can’t use violence.”

The true reclaiming of what it means to be an indigenous person is spiritual. This means one must return to the essence of being a true warrior, in the sense of “they carry the burden (of their heritage).” It is about having strength and integrity inside yourself to be an authentic person, carrying yourself with a sense of justice and rightness.

“Colonialized peoples need to recreate themselves as people who are spiritually-grounded and strong, in order to withstand all those forces of assimilation and recreate the something new out of the best values of the indigenous culture. The most impressive thing that Ghandi did was to take a stand against both imperialism and traditionalism, and insist that people needed to create something new out of both appropriate to today. This is really the solution.”

Meanwhile, what can be done about growing problems among youth? There are increasing levels of drug use, violence, and family violence. Smoking is increasing, gun and gang culture are emerging in Canada. What about indigenous people in the urban centers?

“We need to create relationships between those people and the home communities. However, many of those home communities themselves are problematic.”

More indigenous people in Canada are going to university and becoming doctors and lawyers. Taiaiaka’s view is that each day of his life, no matter what job or education level an indigenous person receives, he can make the choice to support either the vision of indigenous people, or the vision of the colonizer. Taiaiaka hopes to inspire the next generation of indigenous leaders to regenerate the culture in a political and legal manner, to force Canada into a reconciliation with reality. He envisions a social and political agenda in Canada like the Black Civil Rights Movement in the United States. The goal is to recover the stolen sense of what it means to be an indigenous person living the authentic life of our ancestors.

For all recently decolonized peoples, the way forward is to find a middle road which is neither the vision of the colonizer, nor a reactionary vision against the colonizer. Decolonized peoples must take what is useful from the colonizer and combine it with a spiritual vision from their own culture to find a new way forward in the modern world–to be part of the modern world, while not “of” the colonizers’ world.

With regard to national cultures which are trying to assimilate native cultures through the use of education and materialistic recompense, I feel this strategy is far preferable to the ethnic cleansing which is happening in so many parts of the world (which is what happens when assimilation efforts fail). While I can understand the pain of native peoples, I think adapting to the dominant culture is probably the best middle course of action for all.

–Lynne Diligent

Tags: assimilating cultures through materialistic recompense, Black Civil Rights Movement in America, Canada's Inuit problem, Canadian Inuit assimilation problems, Colonized peoples don’t want to be part of an integrative relationship., Dr. Martin Luther King's Black Civil Rights Movement, Psychological anger over colonization by colonized peoples, Taiaiake Alfred, why native peoples like and respect treaties rather than assimilation

December 12, 2011 at 12:43 pm |

Posted in reply by Bruce Stewart (Canadian) – 12:19 PM – Google Reader – Public

“I think we need to keep in mind three things:

(1) None of us are immune to the effects of what Thomas Langan (Tradition and Authenticity, Being and Truth, and Surviving the Age of Virtual Reality) called the corrosion and dissolution of our traditional societies in the face of the global overlay he called the HTX. This has (as noted by George Grant) undone traditional French and British Canadian societies of the south just as much as it has undone the traditional societies of the First Nations and Inuit across the country.

(2) We have begun a path to understanding how to implement traditional governance inside the Canadian Confederal framework — Nunavut is under Inuit law (neither common law nor civil code), for instance — but the steps are difficult for all concerned because everyone has adopted the notion of territorial control inherited from the West. We need (all of us) to learn how to overlay, share, create communities without demanding territorial controls (for the overlapping claims of all concerned exceed what’s available).

(3) In A Fair Country, John Ralston Saul claimed Canada was not a European nation, but a three-way integration of First Nations, French settlers and English-speaking settlers (deriving from British and American traditions). Certainly our institutions and constitution do not reflect this, nor is it taught to allow future generations to consider how to reform in its direction.

Thanks for sharing this.”

LikeLike

December 12, 2011 at 12:46 pm |

Posted in reply on Google by Bob Macdonald – “Almost lost me with the suggestion that America has ever done anything altruistic but I persevered and there are some excellent ideas about ways forward with First Nations communities – 12:29 PM “

LikeLike

December 12, 2011 at 12:58 pm |

I think part of the problem in Canada is geography. Numbers quoted on the internet vary, but anywhere from 75-90% of Canadians live within 100km of the US border, whereas most of the indigenous settlements are in remote northern areas literally thousands of kms away. The two groups just don’t know enough about each other.

LikeLike

December 12, 2011 at 10:42 pm |

I think what you say makes a lot of sense, Judy.

LikeLike

December 12, 2011 at 11:06 pm |

I think colonization damages the psyche of a nation and this can last for many generations in the form of an inferiority complex. This is what has happened in Ireland; thankfully they are getting over it now and the country is a lot more confident than it was even a couple of decades ago .

I don’t think it is possible to turn back the clock and reclaim a lost heritage; what’s gone is gone. Nobody can remember what the original culture was like so experts create this artificial version which they try to force onto the public. There is also the reality that all cultures evolve to the needs of the modern world so it is hardly practical to try and adopt one from 700 years ago. There is also the tendency to cherry pick those aspects of the past that are comfortable to people today. This is why there is no rush to reintroduce the pagan religion even though Christianity was a foreign import.

My country of birth has wasted a lot of time and money trying to reintroduce a culture and language that is dead. Despite almost a century of compulsory Irish language lessons the vast majority of people can barely speak a word of it. The government could have put that money to much better use in my opinion. The other problem with focusing so much on the past is that it makes people feel a bit ashamed of what they have now.

LikeLike

December 13, 2011 at 12:15 am |

Thanks for your thoughts on this, Paul. I have an American friend who lived in Ireland for 30 years while the re-introduction of Gaelic took place, and she seems to think they have made great progress with the language not being lost.

I think one reason the Arabic world and North Africa have seemed to be be moving backward since the 1960’s was because of the policy of Arabization (trying to get rid of French as the main language of cultured people, as the language of the colonizer). However, the world is not moving in the direction of Arabic. There seems to be a recent turnaround with the introduction of English into public high schools about ten years ago. Now, many, many more people are learning English, the language of world commerce, and I think this is a very positive step for French-speaking North Africa.

LikeLike

June 17, 2012 at 6:06 pm |

After reading this book, it explained SO much about what happened in Canada, and why things are the way they are: http://hiddennolonger.com/

LikeLike